Disney World and Coronavirus

By Dave Shute

WALT DISNEY WORLD IN THE ERA OF CORONAVIRUS

Last updated 3/22 11a EST.

Dear Niecelet 2.0:

I’ve been having fun helping you plan your May 2020 Walt Disney World visit with the Hubs and The Beast.

Then you asked me whether the Coronavirus COVID-19 outbreak ought to affect your plans, and then Walt Disney World announced it was shutting down Monday through the end of the month, and I stopped having fun.

My best guess is that limited operation will being no earlier than Monday May 4…

As you know, I have neither clinical qualifications nor epidemiology training.

But I do have a Twitter account, and from what I can see, that apparently qualifies me to pronounce on the novel Coronavirus, and the illness associated with it, COVID-19.

So here’s some thoughts…

CORONAVIRUS COVID-19 AND WALT DISNEY WORLD: THE BASICS

Last year the U.S. saw about 2.8 million deaths, and in February there were about 5.8 million unemployed.

What will the equivalent numbers be at the end of 2020? Well, that’s kind of up to you.

Take care of others. In the absence of perfect knowledge about your infectious status—which we will never have, as even if you were tested today, you might get infected tomorrow—the ethical thing to do is to act as though you have the disease. The central point is to maintain social distance, especially in settings when you will be with (relative) strangers.

The vast majority of folks who get the disease will recover after mild or unnoticed symptoms, but some folks—especially the elderly, and those with heart disease, diabetes, lung disease, or a compromised immune system—can be horribly vulnerable. (In South Korea, 89% of deaths have been from those 60 and older, and 97.4% of deaths from those 50 and older. China data, which is less complete, shows 81% of deaths from those 60 and older, and 94% of deaths from those 50 and older.) When you see others, you can’t assume that you know the vulnerability of either them or those they are in close contact with. So act as though you are infectious, and act as though those around you are at risk, by maintaining social distancing.

As much as possible, don’t separate yourself from the economy. If you spend less, other people take in less. Then they spend less. And so it goes, and the economy tanks, and a lot of people lose their jobs. Go to the movies if they are still open (while maintaining social distance). Spend some money. It’ll be OK. And if you have liquidity in your retirement plan, buy stocks. Don’t sell them—at your age (even at my age…) that’s what fools do. The rule is sell high, and buy low. Fools do the opposite.

There is much energy that has emerged over the weekend to “just stay home.” The death rate per million people–so far–ranges at the country level from around 2 deaths per million people in South Korea, to 2.3 per million in China, and to 80 deaths per million and rising in Italy. In an average year, each of these countries sees on the order of 7,000 to 9,000 deaths per million people. So the actual increment to what is typical is not a very large number, especially for China, which is pretty much done with the disease–at least so far…

Our policy makers are advising us more and more in the U.S. to just stay home as well. Where we diverge, pay attention to the policy makers, not your uncle!!

Of course if you are diagnosed, this all changes. If you actually have the disease, stay home unless a health care professional indicates that you are one of the 15-20% of people sick enough to be hospitalized.

Take care of yourself. The most important thing you can do is frequent, effective hand washing. There is much fussing about the shortage of hand sanitizers. Carry hand sanitizers (and surface sanitizers) if you can, but remember that soap and water, even cold water, when properly applied and properly scrubbed, is totally effective. Carry a bar of soap with you. Moreover, as you know from the fact that one of your extended family is immuno-compromised, when you have the choice, soap and water, when done correctly, is more effective than hand sanitizers.

One of the poignancies of the present moment is that heightened action led by panic is good for epidemics but bad for people’s jobs. Heightened panic that leads to a lot of extra social distancing, hand washing, and other measures protective of others or yourself will limit the impact of the pandemic at any given moment, reducing the burden of disease on our people and the risk of overwhelming our health care system. But panic as applied to economic activities does not have this positive result. It has really bad results. So find the line where you take care of both your health and the health and jobs of your fellow citizens.

And especially don’t panic over kids. Lotsa places are closing schools. That’s not because kids are vulnerable—unusually for respiratory diseases, they aren’t. None of China’s deaths into February were of kids. None of South Korea’s deaths through yesterday were of kids.

And it does not seem that kids even get the disease at particularly high rates, although there is contention over this. The Diamond Princess epidemiology—the only 100% testing regimen we may ever get on this disease—suggested that kids get infected at the same rate as everyone else. In contrast, simple algebra applied to the South Korea data suggests kids 0-9 years old get the disease at a rate of about 20 cases per million, or about one in 50,000 kids, while everyone else in South Korea gets the disease at a rate of about 171 per million, or about one in 6,000 folks 10 and older. However, the Diamond Princess was an artificial hothouse of infection, so a Bayesian would put the predominant weight of his or her prior on the South Korean data.

The issue with kids is their lousy ability to implement social distance, sneeze hygiene, and the like, especially around their grandparents. Removing them from mixing in masses with other kids in classrooms, school cafeterias, recesses, and buses limits their probably already low chance of getting the disease, which limits their chance of spreading the disease.

CORONAVIRUS AND WALT DISNEY WORLD: YOUR FAMILY AND SOME NUMBERS

There are some really silly numbers out there, mostly well-intended. Numbers that should be posed as “might be, based on the assumptions of our model, if there is no action by anyone” get converted into statements about what the future will be. And hardly anyone but professionals is framing their statements to the true probability ranges of their estimates—and some professionals aren’t even doing that.

Professionals need to model as best they can, even with limitations on present data and imperfect historical analogies. This gives them a range of possible outcomes if there is no material mitigation, and then also a range of possible outcomes after interventions of various degrees of effectiveness (interventions include not just what the government does, but also and much more importantly what you do—remember that what happens next is up to you).

They can then use their model outputs to persuade policy makers and the American people why they should do such things as encourage people to commit to social distancing, close schools, etc.

However, there are some problems with this. Many people—even the best analysts—are not as good as they should be at recognizing that when they are working with samples (either of data or of historical analogies), that the range of “all possible outcomes” is usually much wider than their samples would lead them to first think.

Another key other problem is that intrinsic to epidemiologic modeling are uncertain parameters and exponential curves of growth. Anyone who has ever built such a model understands how wildly sensitive they are to the assumptions used to create them.

That means that good models present such a wide range of possible outcomes that, to those who are not sophisticated on these matters, which is almost all of us, the results don’t appear credible. The uncertainty is real, and is a result of not bad modeling, but good modeling.

Finally, even good modeling can be communicated badly. That happened this week in Ohio. Amy Acton, M.D., the Director of Ohio’s Department of Health—who I think the world of, and am thrilled is leading Ohio’s efforts—said Thursday that “We know now, just the fact of community spread, says that at least 1 percent, at the very least, 1 percent of our population is carrying this virus in Ohio today. We have 11.7 million people. So the math is over 100,000. So that just gives you a sense of how this virus spreads and is spreading quickly.”

Many of those literate in math and the state of the disease elsewhere were immediately enboggled. Ohio has therefore more cases as China, which has been fighting this disease for months? Now, I know that China has particularly bad incidence reporting, but let’s say that there are four times as many people who got the disease as China as reported—that would put the number in China, a country of 1.4 billion people which essentially spent a month doing nothing, at 325,000. So Ohio, with 0.85% of the population of China, has 30% as many cases?

Friday she walked this back, saying “I am not saying there are absolutely for certain 100,000 people, I’m saying I’m guesstimating.” She also explained the analytics of her approach.

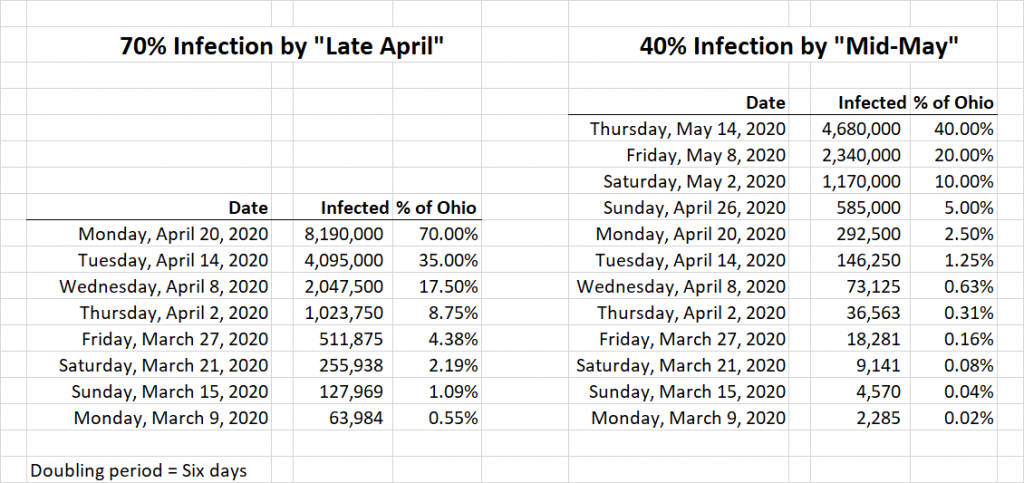

- She inferred from her conversations with many other experts that the estimated range of possible infections, if there was no intervention, was 40% to 70% of the population (you’ll see this many places, but all too often without the qualifiers “estimated” and “if there is no intervention”).

- She also inferred from many other experts that based on the timing of things in Ohio that “the peak would be in late April or early May.”

- She also inferred from many experts that the doubling period, with no intervention, was five to seven days, so she picked six days.

- She then—if I got her analytic approach right—did her math on the assumption that with no interventions 70% of the population would have the disease by late April, and cut this in half every six days until she got to March 9, which was the day she was trying to forecast.

I tried to replicate this analysis—assuming that I heard her correctly.

I got the result as being ~64,000 infected people on March 9, which is quite sensibly rounded to the 100,000 people she noted.

There’s (at least) one problem with this. The problem is that she did not articulate the uncertainty—that is the range of outcomes—of her own stated numbers. Using her same conceptual approach, but picking the two other terms she posed—a 40% infection rate with no interventions, and a mid-May peak—you get a very different answer: about 2,300 people currently infected.

But the biggest problem was the statement “We know now…that at least 1 percent of our population is carrying this virus in Ohio today.”

You can easily model the twelve scenarios that come from her three parameters (two peak dates times two peak rates times three doubling rates*).

And you will get from that work that she should have said not “we know that 1% of our population is carrying this virus today” but rather “the best model I have been able to put together predicts that there are between 300 and 120,000 people infected with this virus in Ohio today.” (The broader range comes from the other two doubling periods.)

That’s a tremendously uncomfortable range for those naive in the sensitivity of exponential models to initial assumptions. But it is probably in the neighborhood of the real uncertainty.

What does this mean for you and your family? Can I give you point forecast? Sure, but remember my qualification is a twitter handle, so take it with a huge grain of salt.

Countries well into this disease are showing a range of infections per million population from ~50 per million to 400+ per million.**

Reported infection rates are highly sensitive to testing rates, as a lot of testing will show many asymptomatic folks that will be missed from infection rates that include only limited testing (and presumptive cases from empirical diagnosis). So to fix an upper end—while making the math easier—let’s use an infection rate for the US of about double that of Italy, so 1,000 per million, or one in a thousand. So that’s your chance of getting the disease—assuming a lot of interventions by both us and those we chose to lead us, but with worse outcomes so far than others are getting.

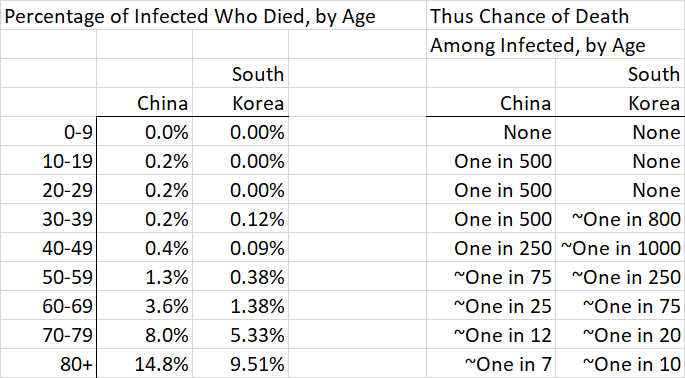

People the age of you and your husband have, in the data from China, about a 0.2% of dying, having gotten the disease, or one in 500. So my point forecast of your chance of dying from COVID-19 is the multiplication of the one in a thousand chance of getting the infection times a one in five hundred chance of dying from the infection once you have it, or one in five hundred thousand. Note that we have not lived with this disease long enough to know much about recurrence: the likelihood of its recurrence, the virulence of its recurrence, the periodicity or seasonality of its recurrence, and the impact of any new herd immunity that will exist during those re-occurrences. So your lifetime risk of death from it is likely to be higher than this.

Those of other age groups (and those with co-morbidities) face different odds. In China, no one the age of The Beast (zero to nine years old) died in the data set that covered through February. The data from Korea shows a much lower chance of death, and that from Italy, where the natural virulence of the disease among Italy’s vast proportions of elderly had been amplified by a collapse in the capacity of its health care system, a higher chance.

Here’s the Chinese and South Korean data, as a percent and expressed as chances of dying:

Another way to think about this. If you are under 60 you have hardly any chance of dying. If you are under 60 and have no major co-morbidities (heart or lung disease, or diabetes) then it’s even lower. So your goal is to prevent infecting those over 60, those with co-morbidities of any age, and those who might be in close contact with them. Which might be anyone…so back to social distancing.

Note that social distancing and other interventions have two different goals.

The first is to spread the burden of the disease on a population over time—thus reducing peaks. This has many positive outcomes, of which the most important is reducing the stress on the limited resources of our health care system. When we run out of resources—health care providers in general, healthy health care providers, protective gear, ventilators, respirators, safe spaces to treat people—more people die.

The second is ideally to reduce the total number of infections. Social distancing, reductions in mass gatherings, and reductions in smaller gatherings that include mixing of people who are not normally in close proximity (like school cafeteria lunches), and home quarantine for the 80% or so of people who are diagnosed but not ill enough to be hospitalized, limit the opportunity for person-to-person transmission.

While it’s pretty widely thought that we can “flatten the curve,” as it is called, from these mitigations, it’s not yet clear whether with COVID-19 we can actually limit the total number of people eventually infected. This is because it takes so long after infection for symptoms to first appear, and symptoms in so many who show them are so mild that they are not noticed. But time, even if it does not immediately reduce total infections, potentially buys us other things in addition to reducing the strain on the health care system. It lets the supply chain of protective equipment and sanitizers refill; it lets ill health care providers heal; it creates the opportunity for the virus to mutate into a less dangerous strain; it perhaps lets some herd immunity emerge.

So social distancing and other measures may or may not limit the total number of infections. What it will do—if people behave ethically–is spread the disease out in time. That—and testing—brings us back to Disney World.

CORONAVIRUS AND WALT DISNEY WORLD: TESTING

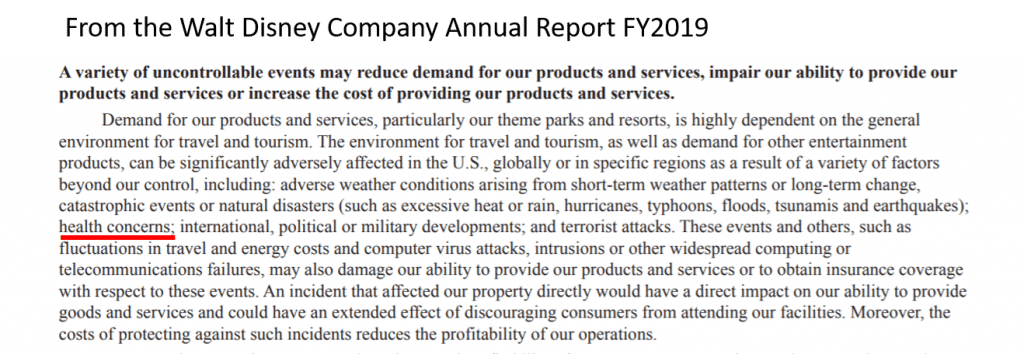

Walt Disney World, and to an extent the Walt Disney Company itself, are basically in the mass-gathering business. Think of Casey’s Corner, the tapstiles before rope drop, the stretching room at Haunted Mansion. Who woulda thunk that Disney+, conceived as a cord-cutting hedge, actually turned out to be a pandemic hedge….

My current best guess is that the only way Walt Disney World can operate while the virus is still a concern is by reducing and organizing its capacity to enable social distancing, and reducing its hours to enable overnight deep cleaning. You’ve probably seen this sort of thing already in movie theaters, where many have taken half or more of their seats out of capacity so that folks on average won’t be as close to strangers as they would have been otherwise.

This would require, I think, severe limits on entry to the parks to enforce a much lower total number of people in them, perhaps closure of some options where social distancing is hard to control (e.g. the afternoon parade at Magic Kingdom, the fireworks shows at Magic Kingdom and Epcot), and marking on the ground in the queues and waiting areas (like the pre-show areas) to indicate where groups should center themselves, so that social distancing from strangers is easy to do.

Other ideas being rumored are more use of Boarding Groups (apparently being re-named “Virtual Queues” and of course limits to the seating in table service restaurants and moving counter service restaurants to mobile orders only.

The other thing that would be of great advantage to Walt Disney World would be widespread testing that is available without a doctor’s order, that produced a dated certificate that could be displayed at the gates (and is hard to forge…). I actually hope for a day when we all wear lanyards containing a card that shows we were disease free at the time of testing, with color coding to indicate the date of testing. This would give people more courage to do the kind of things that would get the economy going again.

You could get most of the benefits from this by imposing a health check–a quick review of symptoms, travel history, and the taking of temperatures–at or before the security checks. A them park in Singapore has remained open with this approach. But that will miss the pretty high proportion of people with the disease who are asymptomatic (more than half in the Diamond Princess data, which is the only 100% sample there is).

There is, as you know, much nonsense being written about testing. Now let me be clear: more testing is better than less testing, and a lot of testing is better than some testing. But this is largely for economic, not clinical reasons, and people who confuse the two might be making foolish errors.

For example, I just saw a tweet—were it not my only qualification to be writing you, I’d be off Twitter entirely right now–that says “logic says we need universal testing but sadly that’s not happening.” Well, let’s spend a moment not being silly. South Korea, which has been universally praised for its testing levels, and held up to scorn us, has tested about 4,000 people per million population. That means that the universally praised South Korean model has NOT TESTED 99.6% of its population.

Or you see dangerous idiocies like this in an AP story about keeping the crisis from overwhelming hospitals, published a day or two ago: “How bad U.S. hospitals will be hit is unclear partly because bungling on the part of the government has left public health officials uncertain as to how many people are infected….Experts fear that when the problems with testing are resolved, a flood of patients will hit the nations emergency rooms.”

OK, let us not be silly. Testing has nothing to do with whether or not you go to an emergency room, and only a fool would suggest that it does. Just as with every other illness in the history of the universe, it is symptoms and risk factors that lead you to the health care system. If you have a fever, dry cough, or shortness of breath, call your primary care office. On that call you will be taken through your symptoms and medical history, and you will hear one of several next steps, depending on your differential diagnosis, the severity of your symptoms, and the presence or absence of other risk factors like age and key co-morbidities. These might include testing. They might include going to the emergency room. But they probably won’t, because most of us don’t have the disease, and of those that do, most don’t need to be hospitalized.

It is darling to listen to otherwise somewhat sensible reporters assume that if someone is not diagnosed via testing with COVID-19, they can’t be treated at all, as I did this evening with an NPR host. Our clinical professionals are not that stupid. If someone has signs and symptoms of respiratory distress, they will get treated for respiratory distress. If some is suffering from viral pneumonia, they will get treated for that. The cause is not a requisite to treatment. And if we are all wise enough to act on social distancing, that is, as though we carry the disease, then the presence or absence of an actual diagnosis matters much less.

What more testing, and more accessible testing, and more speedy results, could do is reduce the risks that others will be infected, and especially if results are visible, as in my lanyard notion above, they would improve the economy by improving the willingness of people to go back out into the marketplace.

More testing would yield more identification of those infected but asymptomatic, who could then be isolated at home and even more than social distancing limit their chances of infecting others; more visibility into who is demonstrably disease free (at least as of their testing date, which is why I suggested the date-of-testing color coding noted above) would improve the willingness of others to be around them.

Disney World may not be back in full routine operation until this disease has run its course—and that is more likely to be well after your May date than before your planned visit.

But it may be able to do a partial opening in April, with limited access and shorter hours (and some attractions not re-opened), so long as it can figure out a way to guide people to social distancing, e.g. by reconfigured queues, boarding groups, paint marks on the ground telling you where to center your party, etc.

Older front of the house cast members, and those with risk-creating co-morbidities, may need to be moved to the back of the house roles for their own safety, and some high-contact jobs—like the cast member in the Haunted Mansion stretching room—may not reappear.

After that, the return of Disney World—and the rest of the economy—to full operation may hinge a lot on how quickly more universal testing is available, as that is what will build confidence in people to be around strangers.

So what’s good for Disney World is good for the world…but the most important thing is that what is next is up to you.

*Since in her analytic approach, the beginning and end dates are fixed, changes in days-to-double changes the number of doubling periods. More doubling periods means fewer cases today, and fewer doubling periods means more cases today.

**Yes, I know that it is much higher in the worst-affected areas. But as a Bayesian I would start with my prior as the national rate, and then revise it up or down based on material local factors. On average across the US this is an OK place to start. The key here to keep your eye out for is if, rather than the disease disappearing from China, as it has been for weeks, if it flares up again to Wuhan levels in a new geography. That would demonstrate a much more dangerous illness.

SOME SOURCES

China data

South Korea data

Testing rates per million

Infections per million

Follow yourfirstvisit.net on Facebook or Twitter or Pinterest!!

2 comments

Have you seen Dr. Michael Lin’s “LinCOVID-19SARS-CoV-2” piece and if so what do you think of it. I liked your thoughts and observations here. Good analytics.

I am an RN and do work with hospital infection control. You have some good research and reasonable estimates based on that. I might venture that your staged reopening is a week +/- within a public health okay for reopening of public spaces like WDW. At any rate we personally are moving April trip to mid August and hoping that WDW is as close to normal operating as possible but before standard flu and a possible 2nd wave hit. I will gladly take a chance with heat, humidity and hurricanes for the chance to actually go this year. Thank you as always for your insight.

Leave a Comment | Ask a Question | Note a Problem