WHAT’S AN “E” TICKET AT WALT DISNEY WORLD?

WHAT’S AN “E” TICKET AT WALT DISNEY WORLD?

I’ve had fun recently writing about “E” Ticket rides at the Magic Kingdom–e.g. here, here, and here.

The phrase “E” Ticket lives today as a metaphor, standing for that which gives rise to a superlative experience.

But it used to be a real thing–the ticket that allowed you on to the newest/best/most popular rides at Disneyland and the Magic Kingdom.

I’ve been noodling a bit lately about the “E” Ticket’s journey from object to metaphor, the negative implications of its physical absence, and the potential of Disney’s NextGen project to bring its absent presence back to concrete reality–though in a different form.

Some other influences on this thinking have been rumors of World of Color coming to Downtown Disney, some light recreational reading I’ve been doing on saving American capitalism from the current model for running publicly-traded companies, and some consulting work I’m preparing to do on recasting physician compensation models so that MDs are paid for the value they create, rather than activity.

In what follows, I’ll pull all this together–and I promise that, as unlikely as it may seem now, it’ll be at least a “C” Ticket experience!

“E” TICKET RIDES YESTERDAY AND TODAY

“E” TICKET RIDES YESTERDAY AND TODAY

The original price model for Disneyland combined a park admission price with individual ride prices. One paid to enter the park, and paid more for the tickets used to actually gain access to the attractions.

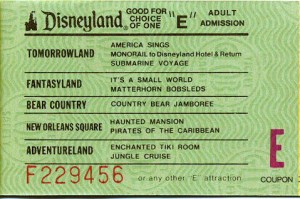

Each ride was classed, and each class had a ticket and associated price. Disneyland began with class “A,” “B,” and “C” tickets, added more expensive “D” tickets at its first major expansion, and even more expensive “E” tickets at its second. The original “E” ticket rides included the Matterhorn and the Monorail.

Tickets were sold both individually (“Dad, I want to ride it again–will you get us some more “E” Tickets?”) and in books that contained varying numbers of the different types– a few “A”s, a few “B”s, etc.

This led to operational complexity–ticket printing, selling and collection–but no one saw it as such, as no one understood there was an alternative.

But in this sea of paper, complexity and labor, there were some advantages.

ADVANTAGES OF THE OLD “E” TICKET SYSTEM

One advantage for first time visitors was that the ticket levels (and associated increasing ticket prices) gave some sense of the relative quality of the attractions. This helped with navigating the park.

Simply, an “E” Ticket was likely to be more fun than a “C” ticket, a “D” Ticket more fun than a “B” ticket, etc.

Many families took the approach of riding all the “E” and “D” attractions, buying extra tickets in addition to their coupon books to do so, but riding only as many “A,” “B” and “C” rides as came in their coupon book.

Disney’s current FASTPASS system plays a bit of this role in marking some exceptional rides today, but is widely misunderstood by first time visitors. Moreover, not all the current “D” and “E” rides are on FASTPASS (at least today–NextGen will likely change that).

Of course, “E” tickets themselves were never perfect guides to distinctive quality–note that the Tiki Room is on the mid-70s “E” Ticket example above, and the rides listed on the first “E” Ticket included not only the Matterhorn and Monorail, but also the Santa Fe & Disneyland Railroad…

The second advantage of the old system was forcing a variety of attraction types. The model of “A” through “E” tickets requires, of course “A” and “B” and “C” attractions. You can still see such at the Magic Kingdom in the vehicles on Main Street, and rides like Astro Orbiter.

While these “A”-“C” rides don’t attract many riders, they add a certain variety and vitality to the parks. The Animal Kingdom is the example of the opposite…pretty much everything there is a “D” or “E” ticket. Part of the point of Joe Rohde’s design for Dinoland U.S.A. was to bring back some of the vitality of a landscape with “A,” “B” and “C” rides.

The third advantage of the old system was providing another way to ration capacity in addition to willingness to wait in lines. Tickets mean that higher demand than capacity at a ride can be solved through increased prices rather than just longer lines–e.g. shifting a ride from a “D” Ticket to an “E” Ticket. Too little demand for a ride can be addressed by lowering prices–shifting a ride from a “C” to a “B” Ticket. Such a ticket system intrinsically does a better job of reducing waits at high-demand rides or filling rides with excess capacity like Carousel of Progress than wait times alone.

But probably the most important advantage of the old system was its impact on how capital and operating budgets were viewed.

The Disney park business model used to be pretty simple.

Adding a new wonderful ride drew on capital and added operating costs to the parks. But doing so also added revenue, as more “E” Tickets would be sold.

The added sales would not be the same as the total rides of the new ride, since there would be some cannibalization of the older “E” Ticket rides. That is, some people would buy no more “E” tickets than they would have without the new ride, and instead just ignore some of the other “E” ticket rides while riding the new one. But other guests would ride both the other “E” tickets and the new one as well, and the upshot was an increase “E” Ticket sales, and thus in revenue that could be pretty directly attributed to the new ride.

Nowadays the business model is more complicated.

Because a single entry price allows access to all of a park’s rides, a new ride in the short term can simply have the appearance of raising operating costs. Invest a ton, and as a result hurt profitability. The response has been to fix profitability when new rides open by eliminating other rides and their associated operating costs.

For example, as far as I can tell, the Fantasyland expansion did not need to be put in the footprint of Mickey’s Toontown Fair.

For example, as far as I can tell, the Fantasyland expansion did not need to be put in the footprint of Mickey’s Toontown Fair.

There’s land to the west that could have been used instead.

But putting the expansion on a closed Toontown reduces operating costs both during construction and after the Fantasyland expansion opens, compared to leaving Toontown untouched and open.

Jim Hill–who has covered such economics for a long time–has a fascinating recent story that illuminates the economics of these decisions, but in this example with a positive outcome for guests.

When the American Idol Experience opened at Disney’s Hollywood Studios, productions of Fantasmic were cut back, especially during the slower seasons, to clean up the park’s resulting increased expenses.

This resulted in not only massive guest complaints–Fantasmic is huge favorite–but also crushing crowds at the Studios on Fantasmic days from people without park hoppers.

Interestingly, though, the Fantasmic show spot is not used for any other activities, and has its own snack stand and crew of trinket sellers.

No Fantasmic, no snacks or trinkets sold…and as Jim notes, these generate enough funds to roughly cover the incremental cash costs of a Fantasmic show.

Partly because of recognition of this, more Fantasmic shows have been added to the calendar.

This is the kind of direct visibility between costs and revenues that under a “one price admission to all rides model” is now rare at Walt Disney World.

In the longer term, new “E” Ticket rides revitalize the brand, and pay off from first time and repeat business. Everybody knows this. That’s why this stuff gets built. Everybody also knows what the ridership is of a new ride.

But unlike in the days of priced ride tickets, there’s no easy way to tie that ridership to the revenue accounting, and hence to direct profitability. All that’s inescapably visible are the added operating costs of the ride…and because these are obvious, they tend to be what gets managed. While as always the map is not the terrain, over any short term period the math is what tends to get managed, not the thing itself.

BETTER MANAGEMENT AND NEXTGEN TO THE RESCUE?

This article continues here.

Leave a Reply

Be the First to Comment!